Pride makes us artificial and humility makes us real

Part I of thoughts on PB Sean Rowe’s op-ed, "Once the church of presidents, the Episcopal Church must now be an engine of resistance.”

Throughout the next two weeks, I’m going to be sharing some thoughts and questions that spring from Episcopal Church Presiding Bishop Sean Rowe’s July 3 op-ed, “Once the church of presidents, the Episcopal Church must now be an engine of resistance.” My hope is that both the thoughts and questions will spark conversation and even collaboration. Please feel free to use comment or chat to join in. This is Part 1 of 5

+

I want to start by saying I appreciate the Presiding Bishop’s words. My own deep dives and at times the issues I might take with some of them do not change that.

One of the jobs of an institutional church leader is to make statements on behalf of and help chart courses for the institution. It is our job as the people of the church to wrestle with what those statements and courses look like in our own contexts … and also to be in conversation with them.

Too many leaders hide in the safety of silence – in part because anything they say will be picked apart and criticized even (or especially) by those who were clamoring for the leader to “say something!” to begin with. Especially in an age where someone like me who doesn’t have the job responsibilities a Presiding Bishop does can type something up and hit “publish” with the luxury of not having a community of accountability – even writing an op-ed like Sean Rowe did takes some courage, and I thank him for that.

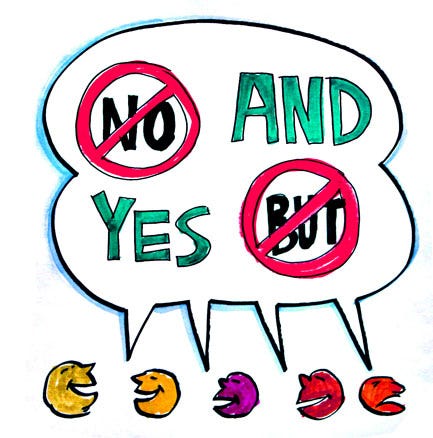

I will try to use a version of the first rule of improv,

Always say “Yes … and.”

Unless I absolutely disagree with a premise, I will try to affirm it and then add new information to build on it and invite conversation about it that will lead us deeper than even the most brilliant op-ed could.

Improv always assumes the goodwill of the other players … and so I hope just as I assume the goodwill of the Presiding Bishop, we can all assume the good will of one another in any conversations that come from this.

+

In this reflection, I want to focus on the first thing in his op-ed that gave me pause … a definite “yes, and”

The Presiding Bishop writes:

“Today, however, we are known less for the powerful people in our pews than for our resistance to the rising tide of authoritarianism and Christian nationalism emanating from Washington, D.C.”

I am learning one of our biggest challenges to faithfully following the revolutionary Jesus is rigorously examining the difference between who we really are and the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves, especially when those stories exaggerate our virtue and minimize the work left to do.

Thomas Merton wrote “Pride makes us artificial, and humility makes us real.”1 The reverse is also true. Artificial senses of ourselves lead to pride, while grounding ourselves in reality leads us to a necessary and holy humility.

When I was Dean of Christ Church Cathedral in St. Louis, I began chapter meetings with a short segment called “As Others See Us” … I would invite people in from local government, from the neighborhood, activists, business people, people who lived in the shelter down the street … and give them space to answer the question “How do you experience Christ Church Cathedral.”

The answers were illuminating … and sometimes challenging. While there were definitely people who said wonderful things that meshed well with the stories we told ourselves about ourselves… there were also those who didn’t. Who gave us a view of ourselves that we would never have gotten if we had just stayed in our own Cathedral or Episcopal echo chamber. It was an invitation to be grounded in reality that, at its best, made us better and more humble followers of Jesus.

When I moved to All Saints Church in Pasadena, a church that had a strong and well-earned sense of its own relevance … I began a practice of talking with people I met as I went about my life … baristas and waiters, cashiers and people who worked storefront counters, etc. … and telling them that I was the pastor at All Saints Church.

What I found was that in the upper-class levels of Pasadena society, All Saints was well known … and admired.

However pretty much anyone under 40 and working in a service position had never heard of All Saints Church. That was appropriate humbling … or should have been.

So when the Presiding Bishop talks about what we are known for, I want to do some data sourcing on that. Is this reality or a story we tell ourselves about ourselves.

The Pew Research Center and other groups regularly do research that would help us with this, so using search engines and AI aggregators I asked the question what the Episcopal Church is known for.

What I got was a real “yes … and” to the Presiding Bishop’s statement.

Yes, among the things the Episcopal Church is most known for is it’s “progressive stand on social issues” … primarily listed among these is our stance on “LGBTQ+ equality.” Also, “gender equality” and “racial justice and reconciliation.”

That’s the yes.

Here is the “and”

Focusing on Pew Research, because it is a trusted data model, here is how their data answers the question of what we are known for when I asked what the Episcopal Church was known as:

· An older, white, and affluent membership, often with high levels of education.

· A publicly influential presence, historically tied to the American elite. Episcopalians are less than 1% of the U.S. population but occupy about 5% of congressional seats.

A champion of social justice issues come in third. We are primarily known as older, white, wealthy and among the political elite.

The data supports this.

*Our congregations tend to be older (44% are 65+) and mostly white (90%).

*Episcopalians also are among the wealthiest religious groups in the U.S> (about 35% have a household income of more than $100K a year – first among Christians and third after Jews and Hindus.

*We also are one of the most educated groups with 33% of weekly attenders holding postgraduate degrees.

*Politically though we are less than 1 % of the U.S. population we hold about 5% of Congressional seats.

And … it doesn’t stop there.

I asked an AI aggregator the question:

“Look for national surveys that ask ‘Can you name the Episcopal Church?’

It returned with this answer:

The Pew Research Center's "U.S. Religious Knowledge Survey" indicates that Americans generally have limited knowledge about various religious groups and their teachings. For instance, fewer than half of Protestants could identify Martin Luther as the person who inspired the Protestant Reformation. This lack of awareness extends to the Episcopal Church, which is a relatively small denomination in the United States.

While specific statistics on public awareness of the Episcopal Church are not readily available, existing research and public discourse suggest that it is among the lesser-known Christian denominations in the United States. This lack of recognition may be attributed to its relatively small size and the similarities it shares with other Christian traditions.

(I invite you to go to ChatGpt or similar AIgreggator and try it yourself)

The reality is simple and predictable.

Most people in this country neither know nor care about the Episcopal Church.

That context is important for at least two reasons:

First, the days where our church and her leaders issuing statements has any widespread impact beyond our own church are over … to the extent they ever existed in the first place.

This is a gift. The PB followed up this statement with a list of institutional actions taken – which I celebrate. And … if we are honest about not only our small institutional impact but even lack of name recognition, we can no longer just “check the box” of following the revolutionary Jesus by association because we belong to a church whose Presiding Bishop … or bishop … or priest … said something.

And … it’s only a gift if we receive it, open it, and take it in. The most disturbing thing to me about the PB’s statement was not in the statement but in the reactions I saw spread across social media. Reactions of chests swelling with pride in being an Episcopalian .. without any sense of an individual or community call to risky and sacrificial action in response to this.

The Episcopal Church as an institution is not poised to be transformational by its words or actions … however individuals and communities are. Which leads me to the second reason this context is important.

Merton’s words resonate with me.

“Pride makes us artificial, and humility makes us real.”

If we can receive the call to courageous action with the humility that comes from recognizing how small and insignificant the Episcopal Church really is, we can begin to have real conversations about how to make a real difference … knowing that just having our primate make a statement isn’t going to cut it.

When we are humble, we can look at ourselves in the mirror … as individual people and as individual communities of faith … and ask questions like:

*How am I/how are we participating in the oppression we are being called to resist?

*How am I/how are we recreating systems of oppression by how our own communities, dioceses and structures operate?>

*Who out there is already leading on these issues – particularly those who are most marginalized and impacted – and what might are call be not to lead but to follow?

*What unique gifts and challenges do I/we bring to a potential movement of revolution that will by necessity have to be bigger than our own church? Who are the partners out there waiting for us to approach them in humility and offer our sacrifice and joy to the movement without an expectation of maintaining power and control?

What are your thoughts? Fears? Dreams? Rebuttals?

How would you answer these questions and what other questions does approaching this moment with humility rather than pride lead you to ask?

Where do you see the gift of the chance to discern the difference between who we are and the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves?

Use the chat and comments. Let’s talk.

Next, Part II: “The reckoning, if we are honest, is long overdue.”

From No Man is an Island, by Thomas Merton — https://www.left-bank.com/book/9780156027731